- TOP

- About Kwansei Gakuin

- History and Educational Philosophy

- L' Esprit de Kwansei Gakuin

L' Esprit de Kwansei Gakuin

L' Esprit de Kwansei Gakuin

> April 2009 -October 2011 > December 2011 -February 2016 > April 2016 -

A Paradox over the Century

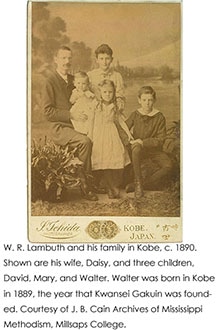

On page 59 of the Centenary History of Kwansei Gakuin, 1889-1989 is a photograph captioned “Memorial Service for W. R. Lambuth.” As a missionary of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, Lambuth founded Kwansei Gakuin at Harada-no-mori in 1889 and left Japan at the end of the following year. While visiting Japan many years later as a bishop, he fell ill and died in Yokohama on September 26, 1921. A memorial service was held at Kwansei Gakuin on October 3, and J. C. C. Newton, the third president of the school, offered a tribute: “He was a citizen of the whole world. He had the world mind because he had the Christ’s mind.”

In the photograph, a long funeral cortège is apparently proceeding from Kwansei Gakuin toward Onohama Cemetery, Kobe, from where his ashes were taken to his birthplace of Shanghai. Closer examination, however, reveals a paradox. The same book depicts the development of the school campus as buildings were constructed one after another. The funeral photograph shows two fine buildings, the Main Building (built in 1894) on the far right and Branch Memorial Chapel (built in 1904) in the middle. The Main Building shows signs of renovation undertaken since its original construction. If the photograph was taken in 1921, Divinity Hall (built in 1912) should be seen to the left of the chapel. Instead, the image shows a wooden building that was in fact demolished ten years before Lambuth died. A fourth building - the first wooden school house - is slightly to the right of the chapel, and a peaceful landscape spreads beyond it.

C. J. L. Bates, the first Canadian missionary to Kwansei Gakuin, noted that the school grounds contained four buildings when he was appointed in 1910. There are certainly four in the photograph, so it must have been taken after March 20, 1908, when the third floor of the Main Building was extended, and before July 15, 1911, when the wooden building on the left side of the chapel was demolished.

The photograph and its caption are thus contradictory. The procession cannot be for Lambuth, who died in 1921. Then, whose cortège was it? According to the records of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, Bishop Seth Ward died in Kobe on September 20, 1909, while visiting Japan.

News of his death was published in the Japan Times the next day, noting that a memorial service would be held at the Kobe Methodist Church (now Kobe Eiko Church) on Wednesday, September 22, at 4 o’clock. The mysterious photograph may well be a sad procession for Bishop Ward leading from the Kwansei Gakuin campus to Kobe Methodist.

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(March 2021)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

Four Eminent Alumni of Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University, founded in 1876, was the alma mater of J. C. C. Newton, the third president of Kwansei Gakuin. In 1884, he entered the university at the age of 36 and attended a seminar on history, political science, and economics offered to graduate students by Dr. Herbert Baxter Adams. Adams was two years younger than Newton himself. Participants in his Seminary of History and Politics pursued their own research themes, reported on their subjects, and criticized one another’s work, regardless of whether they were professors or students.

The Johns Hopkins University Circular, the precursor to the university catalogue, lists those who attended the seminar. Alongside Newton, are three interesting names; Wilson, Sato, and Ota. These men are Woodrow Wilson, later elected the 28th president of the United States; Shosuke Sato, who became the first president of Hokkaido Imperial University in Japan; and Inazo Nitobe (Ota), a politician, diplomat, and author whose likeness was printed on \5,000 bills from 1984 to 2007.

Wilson received his doctoral degree in 1886. As U. S. president from 1913 to 1921, he was instrumental in establishing the League of Nations following the First World War.

Inspired by William Clark, an American professor of chemistry who helped to establish Sapporo Agricultural College, Sato entered Johns Hopkins University in 1883, one year before Newton. After finishing his doctoral dissertation, he returned to Japan in 1886 and was appointed as a professor at his alma mater. Under Sato’s watch, the College became Hokkaido Imperial University, and he served as its president for many years. He is thus known as the father of Hokkaido University.

Nitobe was one year junior to Sato at Sapporo Agricultural College. Following Sato’s advice, he entered Johns Hopkins University in 1884. In May 1887, Nitobe left Hopkins and went to Germany to obtain a doctoral degree from Halle University at government expense. It was his first of five doctorates. He is well known not only as the author of Bushido: The Soul of Japan but also as president of Tokyo Woman’s Christian University and a secretary general of the League of Nations.

Newton helped to found Kwansei Gakuin in 1889. His students deeply admire him as a father figure. Just before his death in Atlanta in 1931, he gave a last interview to a representative of the League of Nations who had come to ask his advice on world affairs.

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(November 2020)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

.png)

Two Newtons for Twinned Departments

In 1889, Kwansei Gakuin was founded in Kobe by W. R. Lambuth, the first superintendent of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (MECS). Strictly speaking, the start of the school goes back to the previous year when a group of theological students, temporarily studying in Tokyo under the leadership of J. C. C. Newton, was merged with a small day school conducted by Newton W. Utley in Kobe. The new institution had both Biblical and Academic departments.

Newton had begun to teach at the Union Methodist Theological School, Philander Smith Biblical Institute, in Tokyo in 1888, but came to Kobe with his seven students the following year. Around the same time, Utley had begun to offer a day class at the Palmore Institute, a night school in Kobe. In January 1889, he opened a regular day school teaching both English language and the principles of Christianity. On September 28, Utley’s school received approval from the Governor of Hyogo Prefecture. Since 1926, Kwansei Gakuin has celebrated its foundation anniversary on this day, but the MECS considers a more accurate date to be October 11, when the twinned departments opened. Newton served as the first principal of the Biblical department and Utley, the Academic. In light of Utley’s first name, Kwansei Gakuin was thus born from two Newtons.

In September 1891, the Japan Mission of the MECS published the minutes of the fifth annual meeting, held the previous month. According to an attached addendum, Utley had been compelled to return to the United States immediately following the meeting and requested that W. H. Wainright replace him as principal. The reason for his departure was not given but earnest prayer, along with two verses of a hymn, was made for Utley’s recovery at the Memphis Conference held in November. Two years later, Utley returned to Japan but was appointed to West Osaka, not to Kwansei Gakuin. In 1896, he finally left the mission field because of the continued ill health of his wife. Returning to his native Kentucky, he studied law and became a lawyer. In 1899, he was elected a member of the state senate on the Democratic ticket.

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(July 2020)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

.png)

D. R. McKenzie and His Friend, Edward Gauntlett

In 1873, the Canadian Methodist Church sent their first two missionaries to Japan. C. S. Eby arrived in a second group in 1876. When he went back to Canada on furlough in 1885-86, he broached the idea of recruiting a band of young men and women to fill some of the numerous English teaching openings in government and private schools in Japan. Their salaries would be paid by the Japanese, rather than by the Church. As far as can be ascertained, fifteen men and one woman had arrived in Japan on a self-supporting basis by the end of 1890.

One of their number, D. R. McKenzie, later became the chair of the Board of Trustees of Kwansei Gakuin. He had left Canada for Japan in 1887 and taught English and Latin at the Fourth High School (Government College) in Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture. He improved his Japanese language so quickly that the Mission asked him to become a regular missionary in 1890.

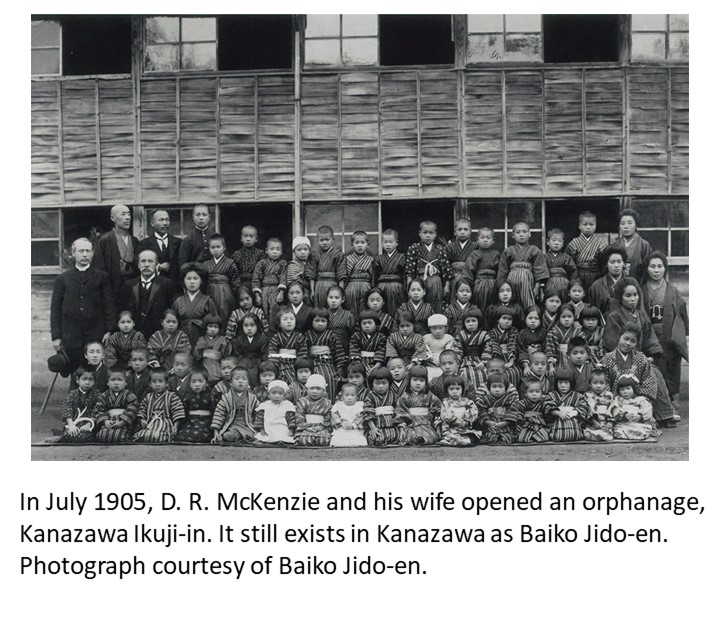

During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, McKenzie opened an orphanage in Kanazawa, the capital of Ishikawa Prefecture. The 9th Division of the Imperial Japanese Army was headquartered within the grounds of Kanazawa Castle, and four months after the war began, it came under the command of General Maresuke Nogi’s Japnese Third Army. The troops took part in the Siege of Port Arthur and suffered severe casualties. Ishikawa Prefecture experienced an average one death per family in the war, leaving many orphans.

McKenzie was on good terms with Edward Gauntlett, an Englishman and well-known organist who came to Japan in 1890 in response of Eby’s recruitment drive. Gauntlett married a Japanese woman, Tsune Yamada. While he was teaching at the Sixth High School in Okayama, his wife’s younger brother, Kosaku, came to live in their household, and Gauntlett taught him music. Later, Kosaku studied at Kwansei Gakuin, then entered Tokyo Music School (present-day Tokyo University of the Arts), went on to Germany, and became a famous composer. Kosaku learned from Gauntlett not only music but also penmanship, shorthand, Esperanto, and ping pong. “Like a blotting paper, I absorbed everything from my brother-in-law,” wrote Kosaku. It was McKenzie who introduced Esperanto to Gauntlett.

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(April 2020)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

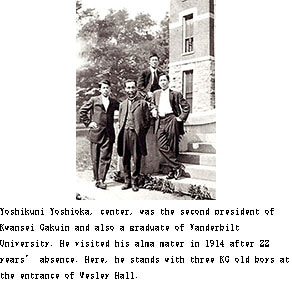

“Fair and Square” and Vanderbilt University

The motto “Fair and Square” has been a very significant for Kwansei Gakuin since its early days. Tamanosuke Nishikawa of the Academic Department provides a wonderful example.

When holding an examination, he wrote the questions on the board and said to his students, “If you have a question, please ask me now. I am going fishing. When you are finished, please put your answer sheets on the teacher’s desk and leave the classroom quietly. The last student should bring all the papers to my house and hand them to my wife or made.” Nishikawa enjoyed good finishing that day and treated every exam in this way from then on. When Ryutaro Nagai who had studied at Kwansei Gakuin from 1899 to 1901 told this story to his friends at Waseda University, no one could believe it. (Nagai later became a famous statesman and held a couple of ministerial positions in the Diet for years.

When I visited Vanderbilt University, Tennessee, in October 2013, I happened to hear a similar story.

Mathematics professor Madison Sarratt told his first-year students, “Today I am going to give you two examinations, one is trigonometry and one in honesty. I hope you will pass them both, but if you must fail one, let it be trigonometry, for there are many good [people] in this world today who cannot pass an examination in trigonometry, but there are no good [people] in the world who cannot pass an examination in honesty.”

The Vanderbilt Honor System was instituted in 1875 with the first final examinations administered.

W. R. Lambuth, the founder of Kwansei Gakuin, graduated from Vanderbilt in 1877. Nishikawa was also there as a fellow from 1887 to 1888.

What happened when a student of Kwansei Gakuin was found to have cheated on anexam? Shintaro Azuma, a professor of the Commercial College, composed a tanka on the subject: “Dean Woodsworth said goodbye, with tears for the cheating student.”

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(February 2020)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

C. J. L. Bates on Television

In the autumn of 1959, C. J. L. Bates was invited to Kwansei Gakuin’s 70th anniversary ceremony. Almost twenty years had passed since the former president of the school left Japan for Canada in December 1940. Although he had made the journey several times by boat, it was his first flight over the broad Pacific Ocean.

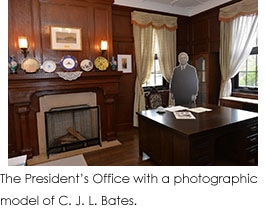

Bates arrived at the fine new airport at Haneda, which was the first of many signs of the country’s remarkable recovery since the devastation of 1945. As his vehicle navigated the crowded road, filled with automobiles and trucks of every description, the ten-mile drive to Tokyo gave Bates further evidence of activity and industry. He learned a new Japanese term for traffic jam, “kotsu mondai.” A couple of days later, he took a night train to Osaka. When he reached Kwansei Gakuin, some 2,000 students were waiting at the entrance gate to give him a boisterous welcome. After their greeting, Bates went up to the President’s Office he had occupied for ten years and took a short rest.

Bates wrote about his experiences over the next three weeks in an article entitled “My Trip to Japan,” after preaching a sermon on the topic at Royal York Road United Church once back in Toronto. Hidejiro Kato, the eighth president of Kwansei Gakuin, then translated the article into Japanese for Boko Tsushin (Alumni Bulletin), No. 23, May 1960. But Bates did not write about every detail of his trip. He left no description of his appearance on television.

At that time, Kiyoshi Hara, a former student of Bates, was an executive managing director at the Asahi Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). On November 2, Bates found himself at Studio 2 of ABC in Osaka as a guest on the program POLA’s News for Women. The program was broadcast on weekdays from May 5, 1958, to September 28, 1966, and the newspaper listing for the show on the day of Bates's appearance has his name in the one o’clock time slot. Kwansei Gakuin Archives holds good photographs in which Bates, 82 years old, bends toward the announcer, Hideko Inada, as he speaks about faith in daily life.

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(October 2019)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

Last Prayer

Before the Second World War, it was common at Kwansei Gakuin to see C. J. L. Bates taking a walk on campus with his wife, Hattie, who was in a wheelchair. Hattie had been crippled on her right side and deprived of speech since suffering a cerebral hemorrhage in 1934. Faculty, staff, and students would feel a warm compassion at the devotion the fourth president of the school showed toward his disabled wife.

After retirement, the couple lived on a pension in Toronto, and in a letter Bates wrote on Sept. 1, 1954, to his daughter, Lulu, “My prayer is that I might be given health and strength to take care of her. That is the raison d'etre for my length of days.”

His prayer was answered. He was able to watch over Hattie until January 20, 1962, when she took her last breath at home.

Not long after losing his beloved wife, Bates had an operation for nephritis and went back and forth between hospital and home. His last hospitalization was two weeks before his death. At that time, Bates said to the Reverend Makio Norisue, “Mr. Norisue, I am afraid that I may not come back home. Please read the 17th Chapter of St. John’s Gospel at my funeral.” Not only Norisue but also his father had studied under Bates.

On December 23, 1963, Bates passed away in hospital at the age of 86. The funeral service was conducted by Rev. Bernard Ennals at Royal York Road United Church. (Many years later, his son, Peter, became a professor of Mount Allison University and taught at Kwansei Gakuin University as a visiting professor in 1986 and 1991.) At Bates’s funeral, the Rev. Norisue read the 17th Chapter of St. John’s Gospel emphasizing the fourth verse: “I have finished the work Thou gavest me to do.”

In 1941, 22 years earlier, Bates had visited the cemetery on a visit to his family home. He wrote his wish in his diary: “I hope to lie there too someday beside my mother and with Hattie beside me and I would like to have Missionary to Japan 1902-1940 carved on a stone marker as well as my name.” When I visited there in the summer of 2012, his gravestone taught me that this wish had also been realized.

【 Click to enlarge. 】

The Lambuths and American Literature

When I traveled north from St. Louis, Missouri, along the Mississippi River in 2013, I made a brief stop at Hannibal, the boyhood home of Mark Twain. Places and people in this small town were depicted in Twain’s novels, which have been read in Japan.

Mark Twain reminds us of David Lambuth, who was the first son of Walter Russel Lambuth, the founder of Kwansei Gakuin. After several of years teaching at Colegio Piracicabano in Brazil to help his father’s missionary work, the younger Lambuth became a professor of English at Dartmouth College. Budd Schulberg, one of his students, described the professor’s picturesque character, “pince-nez, a white professorial beard, a rakish black beret, white ‘Mark Twain’ suit and white shoes, a black opera cape, and a white Packard.” David’s wife, Myrtle, stood out even more than he did in the quiet college town of Hanover. Her absent-mindedness provoked the nickname “Alice-in-Wonderland,” and the titular character of the 1928 novel The Professor’s Wife is said to have been modeled after her.

【 Click to enlarge. 】

Another famed American author, Pearl Buck, also had a connection to the Lambuths. Walter Lambuth’s brother, Robert, was living in Kobe when his daughter Nettie was born in 1889, the same year that Kwansei Gakuin was founded. The following year, Robert, and his family went back to the United States. A few years later, Robert’s wife died and Nettie was sent back to Japan to live with her grandmother, Mary. After Mary died, Nettie was raised in China by her aunt Nora. Pearl Buck, the daughter of a Presbyterian missionary, also spent her childhood in China. When Nettie’s daughter, Jean Lewis, published her first novel, Jane and the Mandarin’s Secret, in 1970, Pearl Buck wrote an endorsement for the dust jacket.

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(April 2019)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

D. R. McKenzie, the Prince of Mission Treasurers

【 Click to enlarge. 】

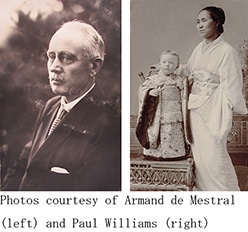

Kwansei Gakuin was founded in 1889 by the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, and in1910, the Canadian Methodist Church joined in its management. The first Canadian missionaries to arrive at the school were C. J. L. Bates and D. R. McKenzie. Two years later, the College Department, Literary and Commercial, was established. Bates became its first dean, proposing the now widely recognized maxim “Mastery for Service,” as the motto for the whole school. Whereas Bates served as the fourth president of Kwansei Gakuin from 1920 to 1940, McKenzie moved to Tokyo in 1913 after helping to establish the financial administration of the school. Nonetheless, he continued to serve on the Board of Directors of Kwansei Gakuin for more than 20 years and for quite some time acted as its chair. He died in 1935 at the age of 74 and rests in peace at Aoyama Cemetery in Tokyo.

McKenzie, 16 years older than Bates, came to Japan in 1887 as a member of Dr. C. S. Eby’s self-supporting Missionary Band. He taught English and Latin at the Fourth High School (Government College) in Kanazawa and gained a considerable reputation. In 1890, he officially joined the Japan Conference. During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904?1905, McKenzie and his wife established the Kanazawa Orphanage. Although he never gave the impression of being interested in finances and statistics per se, he always found opportunities in the financial area for promoting the wider work of the Mission. For that reason, he was known as the “Prince of Mission Treasurers.” P. G. Price described his first impression of McKenzie, who was on hand at Price’s arrival in Japan: “Quite a company had come to welcome us and there was a great deal of leisurely chatting on the boat before landing but McKenzie was after the luggage and wanted to know exactly how many pieces there were and to get things on the move.”

McKenzie, the Prince of Mission Treasurers, and Bates, the educator, worked hand in glove for the development of Kwansei Gakuin.

On December 20, 2018, Dr. Paul Williams donated a kimono that had belonged to his grandmother to Shigeki Kawakami, Director of Kwansei Gakuin University Museum. Pictured here in the kimono is young Ethel McKenzie, daughter of D. R. McKenzie, when her family was living in Kanazawa. Following in his great-grandfather's footsteps, Dr. Williams is a Visiting Professor of Canadian Studies at KGU.

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin

Archives(February 2019)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

An Audience with the Emperor Showa

In the autumn of 1959, C. J. L. Bates, a former president of Kwansei Gakuin, visited Japan with his second son to attend the school’s 70th anniversary ceremony. It was his first time in the country in nineteen years. After the festivities were over, he went to Tokyo to take part in a centennial celebration making the beginning of Protestant Christian missions in Japan. While there he was given a private audience with the Emperor.

Showa Tenno Jitsuroku (The Authentic Record of Emperor Showa) records the November 4 meeting: The Emperor granted an audience to Cornelius John Lighthall Bates, the honorary president of Kwansei Gakuin, in the reception room. Mr. Bates was born in Canada, and devoted himself to private schools in Japan from when he first arrived in 1911 [correctly 1902]. He has also taken good care of Japanese people living in Canada. This time, he visited Japan to attend the 70th anniversary of the founding of Kwansei Gakuin.

Bates visited the Imperial Palace with W. F. Bull, the Canadian ambassador to Japan, who had met Bates at Haneda Airport upon his arrival. Bull and Bates had been asked to come to the palace in ordinary business suits, but it was a big surprise to Bates find the Emperor similarly attired. Bates noted, “The Emperor was most kind. He shook hands with Mr. Bull, then with me and motioned to us to be seated. Then he said to me, ‘I have been told that you spent many years in education work with my young people. I wish to thank you for your service.’ His majesty is one of the most sincere, unostentatious persons I have ever met. No pretence, no airs whatever.”

Bates had served as the president of Kwansei Gakuin for 20 years before the Pacific War. He attended the funeral of the Emperor Taisho in 1927 and received portraits of the Emperor and Empress in 1937. Bates noted in his diary that the Emperor was the center of life of Japan and that loyalty to him was the country’s greatest unifying force. He seemed to draw a parallel between the feelings of the Japanese people for the Emperor and that of Christians who put God at the center of life.

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(October 2018)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

Kwansei Gakuin Finds Fame in a Novel

The novel Omoide no ki (Footprints in the Snow), by Roka (Kenjiro) Tokutomi, was published in 1901 and has taught many readers about Kwansei Gakuin. Kazuo Kitoku, who entered Kwansei Gakuin Theological School in 1910, recalled that the book introduced him to the school. Toyohiko Kagawa, a Christian reformer, noted that he had become aware and fond of Kwansei Gakuin by reading the same novel.

This long narrative was published in serial form in the Kokumin Shimbun, a newspaper that had been started by the author’s brother, Soho Tokutomi. It is the story of Shintaro Kikuchi, born into an old family in the countryside, and it traces his path to independence from his mother’s expectations. After the bankruptcy of the family business and his father’s death, Kikuchi leaves home to attend Kwansei Gakuin in Kobe. There he meets a teacher, Kametaro Kan, whose influence helps him to find his life course.

In the novel, Kan has a good command of English and often bests American missionaries in staff discussions. The character is modeled on an actual person, Genta Suzuki, who taught English at Kwansei Gakuin from 1894 and was the chief editor of the Kahoku Simpo newspaper in Sendai at the time of the novel’s publication. (Sendai also features in the narrative, as Tokutomi makes the head of Kwansei Gakuin a feudal retainer from Sendai Domain.)

Suzuki came to Kobe with the Lambuths from Shanghai in 1886, at the beginning of the Japan Mission of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. He became its first convert and went to the United States to study. Seven years later, he retuned Japan having made the decision to devote his life to mission work and teaching in Kobe. His teaching life at Kwansei Gakuin lasted less than three years, however, just as Kan’s does in the novel. According to Suzuki, his resignation aroused suspicion and hurt his American friends’ feelings.

【 Click to enlarge. 】

It is said that Footprints in the Snow is semiautobiographical. Though Tokutomi himself studied at Doshisha in Kyoto, however, his protagonist attends Kwansei Gakuin (referred to as Kansei College in the English translation). What did the author intend by selecting a different school? We cannot know, but it was a happy choice for readers.

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(July 2018)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

Special Invitation: The Centennial of the Founding of Latvia

When Latvia proclaimed its independence from Russia on November 18, 1918, Kwansei Gakuin was located at its original site of Harada-no-mori and a young Latvian named Ian Ozolin (Janis Ozolins) taught English at the College Department (Literary and Commercial). In May 1920, he began working as a diplomatic and consular agent of the Republic of Latvia to Japan at the request of Latvian government in Siberia and the Urals.

As the representative of the provisional government of Latvia, he contributed an article on his country to the Japan Advertiser, drawing an immediate response from Russia. The Russian vice consul in Kobe wrote a letter to the Hyogo prefectural governor, asking if Ozolin had been officially authorized by the Japanese government to represent Latvia as diplomatic and consular agent. The governor in turn inquired at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and received the following answer: “The Imperial Japanese Government has never approved his status.” Japan had not yet recognized Latvia’s independence.

【 Click to enlarge. 】

Ozolin, however, had a strong desire to make his home-land widely known and continued to write to the press. In January 1921, he wrote to the Japan Weekly Chronicle, “Let me point out, for the benefit of readers that may not be acquainted with the facts, that, of all the ‘border States’ sometime forcibly annexed to the Russian Empire and now liberated, Latvia is the most conservative as it is also the most nationalistic.” He continued, “All this goes far to show how improbable, not to say impossible, is a Communistic upheaval in Latvia.” He ended his article with a warning, “Let me express my surprise at seeing the valuable space of the Chronicle thrown open to malicious canards manufactured by a syndicate of Russian imperialists now on [a] vegetarian diet in the pleasant city of Paris.”

In the classroom at Kwansei Gakuin, Ozolin likewise encouraged his students to take a principled stand: “The young should consider themselves especially fortunate at this moment in the world’s history, because it is they that are particularly invited to build up the new world.”

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(April 2018)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

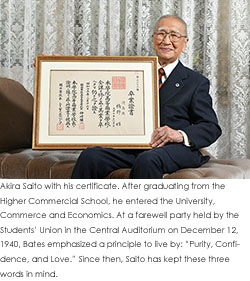

Student and Teacher

“My Higher Commercial School certificate (March 1940), on which President C. J. L. Bates’s name appears, is very special. Here it is.” Akira Saito, soon to be one hundred, showed it to me proudly. His pleasure at the memento is not unique. In 1957, Bates, then eighty, remarked, “Over 7,000 young men, graduates of Kwansei Gakuin, have my name on their graduation diplomas. Many of them write from time to time and thus help to preserve the intimate relation of respect and affection that exists between students and teachers in the Orient.”

On July 4, 1940, Bates’s resignation was accepted by the school’s Board of Directors. Representatives of the Students’ Union responded with distress, rushing into the President’s office to tell Bates that they would visit the directors’ homes to protest. The whole student body then met and swore allegiance to Bates. Shuzo Yasueda, a third-year student in the Higher Commercial School, wrote a letter in English to President Bates, asking him, “Please remain in your present position for us.” Surprisingly, he received a personal reply.

The beautifully handwritten letter became a life-long treasure to the student, and some fifteen years ago, he showed it to me.

“Thank you very much for your kind letter,” Bates wrote. “I appreciate the love of my students more than anything in the world. You are all my dear children whom I love as my own sons.”

The letter ended with prayer: “Let us pray to God, who has guided Kwansei Gakuin through fifty years, to send the right man to lead our beloved school in His name in the future as in the past. I have always tried to remember that God is the real Head of Kwansei Gakuin and that I was His servant. Let us never forget that and all will be well.”

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(February 2018)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

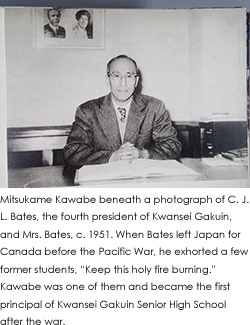

Friendship with the Flying Scotsman

At the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, Scottish athlete Eric Liddell won the gold medal in the 400 metres. Liddell was a friend of Mitsukame Kawabe, a young Japanese man who later became the first principal of Kwansei Gakuin Senior High School. Kawabe’s book Senriyama no Koe (Voices from Senriyama), published posthumously in 1971, records the details of their friendship.

Kawabe graduated from Kwansei Gakuin Literary College in 1919 and studied at the University of Edinburgh from 1923 to 1924. There he met Liddell, who was studying pure science, and they rented adjacent rooms in the same boarding house. Liddell, born to missionaries in Tianjin, China, captained the university rugby team and was a heroic figure around Edinburgh.

One day in 1923, Liddell told Kawabe that he had been selected to run the 100 metres for Great Britain at the Olympics the following year. Kawabe began to help Liddell with his training routines, drawing on his own experience as a sprinter. Kawabe’s stopwatch sometimes showed a world record, but that was a secret between just two people.

The following spring, however, Liddell decided to withdraw from the race because he knew it would be held on a Sunday. Kawabe urged him, “If you run and win on Sunday, you can show God’s Glory,” but Liddell was devout and Kawabe could not change his mind.

In June, Liddell offered to fill a vacancy on the team to run the 400 metres, which was to be held on a weekday. For the next two months, Kawabe and Liddell put all their energies into preparing for the games. Kawabe went to Paris with Liddell and continued to take good care of him. Contrary to expectations, Liddell qualified for the race, and asked Kawabe to pray for him.

With the race under way, Liddell led for the first 200 metres. Kawabe knew very well that Liddell could not keep up such speed, but he prayed wholeheartedly for the runner. Amazingly, Liddell held on, continuing to run at sprinting speed for the last 100 metres and taking the gold medal with a new world record of 47.6 seconds. Kawabe wrote in his book, “I believe in the power of faith, the blessing of God, and the miracle of spiritual power.”

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(October 2017)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

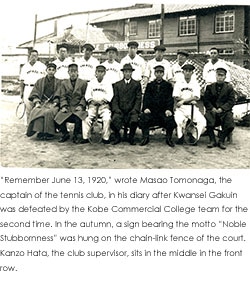

A Student from Matsuyama

When a baseball team was formed at Kwansei Gakuin, Principal S. H. Wainright of the Academic Department provided the equipment and volunteered as a hitter during fielding practice. He attended the games not only to root for the team but also to keep an eye on the players. The students started fights easily and often argued with the umpire.

In September 1897, Kanzo Hata transferred from Ehime Middle School in Matsuyama to Kwansei Gakuin. Before Hata left Matsuyama, Kinnosuke Natsume had begun to teach in the Middle School, but later he became a highly regarded novelist under the nom de plume Soseki Natsume. Natsume wrote Botchan in 1906, based on his personal experiences as a new teacher in Matsuyama, and the book is still widely read in Japan. Hata said that he was familiar with most of the episodes it described.

Before coming to Kwansei Gakuin, Hata had already played baseball, and once in Kobe, he gained some recognition as the first pitcher to throw a curveball. It happened in 1898 in a game against Kenko Gijiku Anglican School (the present-day St. Michael’s International School). Kiichi Kanzaki, one of his teammates and the fifth president of Kwansei Gakuin from 1940 to 1950, described the play: “The Kenko team could not hit Hata’s ball. They thought the speed of his pitched ball was too slow and tried to make a slow swing. A player watching the game behind home plate finally realized that Hata had thrown a curveball and got upset.”

Regarding school work, Hata had enjoyed studying mathematics in Matsuyama. The Ehime Middle School had a very good math teacher, who went by the nickname “Porcupine” in Botchan. At Kwansei Gakuin, the teaching style was completely different, however, and Hata lost interest in the subject. Instead, he became attracted to more philosophical inquiries and began to think deeply about the reason he had come into the world.

Eventually, Hata became an English teacher at Kwansei Gakuin and also ran the tennis club. The club lost matches against Kobe Commercial College twice in succession despite good technical skill, so Hata came up with a club motto, “Noble Stubbornness,” to strengthen the spirit of the players. The words come from the poem “To my Honoured Kinsman,” by the seventeenth-century English poet John Dryden: “Patriots in peace assert the people’s right / With noble stubbornness resisting might.” The phrase has since become the motto for the Kwansei Gakuin University Athletic Association.

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(October 2017)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

A Birthday Resignation

May 26, 2017, is the 140th birthday of C. J. L. Bates, the fourth president of Kwansei Gakuin. He was born at a small village named L’Orignal in Ontario, Canada.

On his last birthday at Kwansei Gakuin, in 1940, at the age of sixty-three, Bates wrote the letter of resignation he would tender the following day. The day before his birthday, he had written in his diary, “O God grant us guidance that we may be able to come through this delicate situation without injury to the spiritual life of the school. Show me what to do day by day and moment by moment that I may not fail to act aright at the proper time.” The genesis of his decision to resign from the presidency can be found in his graduation address of the previous year, in March 1939. His words stirred some controversy, making it evident that Japanese members of the Board believed the school should have a Japanese president. Bates’s distress was apparent for months in his diary.

【 Click to enlarge. 】

The Board received his letter of resignation and a meeting of the K. G. Executive was held in camera on June 17. After some discussion, it was decided that under the national and international circumstances of the time, it would be wise to accept the resignation. Upon hearing the news from W. K. Matthews, an American missionary, Bates wrote, “It has been a great privilege. I have served in this position for twenty years and the time has come to give it up. I had hoped to continue until 1942 but now is the time. We can blame it on Hitler if we need a [scape]goat.”

Bates left Japan from the port of Kobe on December 30. A car arrived at the missionary house to convey the former president and Mrs. Bates to the port. Before making a journey, however, the Bateses drove through the campus from the main entrance and around the central lawn in order to see every inch of Kwansei Gakuin one last time. As the car moved slowly past each building, faculty, staff, and students came out in front to say good-by or make a last bow.

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(October 2017)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

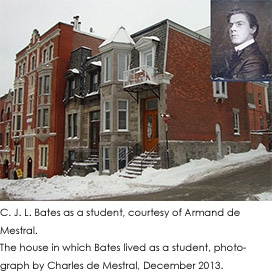

Lorne Crescent and the Crescent Cottage

C. J. L. Bates, later the fourth president of Kwansei Gakuin, studied at McGill University in Montreal from 1894 to 1897. In those days, the city was the commercial capital of Canada, and ships from all over the world docked at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River to discharge their cargoes there.

Kwansei Gakuin Archives holds several books that Bates used as a student. In one entitled Ancient History for Colleges and High Schools: Part I, The Eastern Nations and Greece, his name and address are inscribed: “C. J. L. Bates / Sept. 22, 1894 / 1st year Arts / 21 Lorne Crescent / Montreal.” The little street is situated immediately north of the university campus. That Bates lived on a crescent, rather than more typical “rue,” or road, feels serendipitous, as a crescent moon is the symbol of Kwansei Gakuin. The address therefore seems like the first sign of Bates’s later strong ties with the school.

Charles de Mestral, a grandson of Bates, now lives in Montreal. He turned to Sylvie Grondin, archivist at the National Library and Archives of Quebec, to discover more about the history of Lorne Crescent. Between 1890 and 1909, the highest number on the crescent was 21, so Bates lived at the extreme end of the small street. In 1894, the property was owned by William Edward Doran. Charles took several photographs of the house at the corner of Aylmer Street and Lorne Crescent, concluding, “It is reasonable to suppose that the side door, on Lorne Crescent, corresponds to the address 21 Lorne Crescent of those days. The side door in the photo is now obviously new. In those days, the round top of the doorway may have contained a decorative stained-glass window, now unfortunately no longer there.”

After serving as school president for twenty years, Bates resigned from Kwansei Gakuin in 1940 and returned to Canada. He bought a small house in Toronto and called it Crescent Cottage, clearly as a reminder of Kwansei Gakuin. A cherry tree, one of the trees given to Canada by the Japanese government, was planted in the garden.

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(October 2017)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

The Age of Pioneers, Commercial College

At Kwansei Gakuin, the College Department, Literary and Commercial, was established in 1912. Soon, the students of the Commercial College organized the Commercial Club in order to practice what they learned in class and to deepen their friendships. The first meeting was held on February 23, 1913, and Kichitaro Muramatsu, the first chair of the Kobe YMCA, gave a lecture. From then on, lectures were offered occasionally at the club.

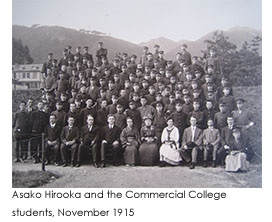

In November 1915, Asako Hirooka (1849-1919), who was instrumental in the foundation of Daido Life Insurance Company and the Japan Women’s University, was invited to speak. (The NHK’s serial television drama based on her life ? Asa ga Kita, meaning Asako, the morning has come ? aired from September 2015 to April 2016 and garnered a high audience rating.)

No written record of Asako Hirooka’s lecture survives, but in the Kwansei Gakuin Archives is a good photograph showing her in the front row, with Hatsune Yoshioka, the wife of President Yoshikuni Yoshioka, on her right, and Hattie Bates, the wife of Dean C. J. L. Bates, on her left. As Kwansei Gakuin was a boys’ school at that time, a photograph showing a woman is a rare find ? let alone one of three women.

The pioneering activities of the Commercial Club did not stop at the lecture series. During the summer holidays in 1913, students visited teachers’ houses to collect funds for the Consumer’s Cooperative Association. And the students were themselves entrepreneurial. Wearing Western clothes, they worked as salesclerks, selling ink and pen, so successfully that they soon had to hire an employee. In those days there were no shops around the campus, only farms. The school’s farming neighbors were famous for their Kumochi white radishes, and on both sides of Kami-Tsutsui Street, later the site of a shopping quarter, were sorghum and eggplant fields.

In February 1915, the Commercial Club published the periodical Shoko. The first issue opened with an address by Dean Bates entitled “Our College Motto, Mastery for Service.” These words, which he proposed for the College Department, became the motto for Kwansei Gakuin as a whole.

These outstanding activities were all initiated by the pioneers of the Commercial College. The first class started with 36 students. Four years later, 12 pioneers went out into the world.

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(October 2016)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

“U Boj, U Boj” by Kwansei Gakuin Glee Club

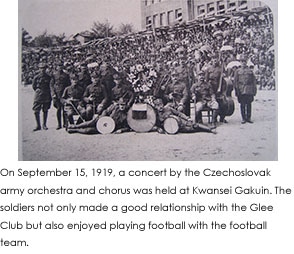

The Kwansei Gakuin Glee Club has the oldest history in Japan, and no recital ends without singing “U Boj, U Boj.” When this special song was brought to the school by the Czechoslovak army in September 1919, the campus was at Harada-no-mori, present-day Nada-ku, Kobe. After fighting in one place after another in Siberia, the army came to Kobe to make repairs to one of its ships. The Glee Club members formed a friendly relationship with the army’s choral group and obtained four music scores, including “U Boj, U Boi.” Since then, this song has been sung only by Kwansei Gakuin in Japan. The Glee Club understood that the song title meant “to fight in battle” in spite of having no information about the lyrics, or even the language in which they were written.

In September 1965, the KG Glee Club was invited to the first International University Choral Festival in New York. At a reception luncheon at the Hilton Hotel, a group of students from Latin America started singing. Following suit, KG members began to sing “U Boj, U Boj.” Then, something astonishing occurred. Some students from Skopje University, in Macedonia, then part of Yugoslavia, stood and joined the singing. It was a dramatic moment for the KG Glee Club to find out that “U Boj, U Boj,” which the Japan had thought of as a Czech song for almost fifty years, was actually from a well-known opera in Yugoslavia. There is an expression regarding Yugoslavia’s diversity: seven borders, six republics, five ethnicities, four languages, three religions, two alphabets, and one federation. It turned out that “U Boj, U Boj” was from Croatia, also part of Yugoslavia.

At the Kwansei Gakuin Glee Club Festival in September 2008, Dr. Dorago ?tambuk, the Croatian ambassador to Japan, stood on stage with students and alumni of the Glee Club to sing “U Boj, U Boj” with them. In October 2012, Ms Mira Martinec, Dr. ?tambuk’s successor, was invited to a recital in Tokyo by Shingetsu-kai, the Glee Club OB chorus group. She was so moved by their rendition of “U Boj, U Boj” that she gave them a standing ovation. I have privately asked each ambassador how well these groups pronounced the Croatian lyrics. Both answered me with a big smile. “Perfect!”

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(October 2016)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

The Commercial School in Osaka and W. R. Lambuth

The New Orleans Christian Advocate was published for the Louisiana, Mississippi, and North Mississippi Conferences of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. The periodical teaches us about the early activities of the Japan mission of the church, because the Lambuth family often wrote to the editor. J. W. Lambuth belonged to the Mississippi Conference and was the father of W. R. Lambuth, who founded Kwansei Gakuin in 1889.

In 1887, W. R. Lambuth was living at Foreign Settlement No. 47, in Kobe. He taught for four hours a day in Osaka and had a further two hours of work at home in the evening. It took him two hours each day to make the round trip. He wrote an interesting article entitled “Seven Doors” for issue no. 1622 of the Christian Advocate, which appeared on September 1st that year. In it he outlined seven urgent requests he had received from Japanese people. The sixth came from Osaka: “I have been requested to furnish a teacher for three schools in Osaka, twenty miles from Kobe, to teach elementary English two hours each day. Salary, ninety yen a month. A Japanese residence provided, and also a house for chapel.” One of the three schools was a commercial school, as Lambuth notes: “The trustees of this school (the commercial school) are said to be some of the most enterprising men in Japan. Chinese (the Mandarin dialect) is taught daily, in view of prospective commercial relations with China.”

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(October 2016)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】

In April 2015, Yutaka Taira visited Kwansei Gakuin Archives hoping to see a book on his school’s history. He was from Daisho Gakuen High School, which is located in Toyonaka, Osaka, and still has a commercial course. Our visitor remarked to me that when the school was founded in 1887, an advertisement had been placed in the Asashi Shimbun newspaper on August 30th and 31st. In it was the name Lambuth, listed among teachers applying for positions. Taira wondered whether this Lambuth, an American medical doctor, was in fact the founder of Kwansei Gakuin. The same advertisement also contained the name of a Chinese-language teacher. Taira’s question reminded me of the teaching opening mentioned in the article by W. R. Lambuth, 129 years before, as our founder was himself a medical missionary.

Yuko Ikeda, Kwansei Gakuin Archives(October 2016)

[Special thanks to Camilla Blakeley for editorial assistance in English.]

【 Click to enlarge. 】